On November 19th this year, Marilyn Certner Smith and I will be presenting on relationship and reflection in aphasia therapy at the national convention of the American Speech-Language Hearing Association in Philadelphia. As usual, we are tweaking slides and engaging in conversation about what it is we want to share up until the last moment. Today, looking at the section on disability and identity, I found some notes that I had written at least five years ago. I’m reminded of times when, sorting through old papers, you find a paper or story you have written that seems so much better than what you can do today.

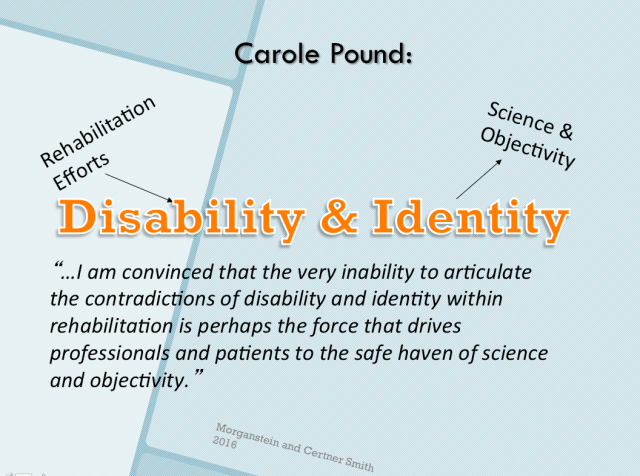

Carol Pound, an aphasia philosopher who worked with UK Connect in its early days, has written extensively on identity. She tells her personal story, in which, as a potential international tennis champion, she is injured, and left with permanent and intractable pain. The subsequent alteration in her life and persona, she felt, was something that made her more vulnerable, and, perhaps allowed her to connect with clients more genuinely.

This slide illustrates a point she made:

And here are my old notes, written in response to her discussion:

This makes sense when looking at the traditional ways we approach therapy: the client is damaged goods, the therapist is the fixer, and the goal is to strive for normal or near normal function. Pound talks a lot about the “seductive” notion of cure. We get sucked into it and so does the person with aphasia. It is a promise we cannot fulfill, but we make it anyway. We spend virtually no time in our training learning how to help people INTEGRATE the new identity of person-with-disability, let alone our own reaction to what that means for us as therapists. It means having to listen to the suffering narratives, the stories of who they were “before,” and accepting that we cannot make the aphasia go away, or we cannot teach compensatory strategies, or a million other things we hold dear in our profession. This, the decade of the brain, is exciting in the projection of a future in which we can zap a cortex and plug it in to exercises and make it better. Is it also perhaps a retreat into the past philosophy of our role as fixers? Are we afraid to go forward into the inner self, accepting disability, and helping others with the new narrative?

In my work at rehabilitation hospitals, I have seen the anger and frustration that builds in speech-language pathologists who deny this reality. They are stymied at what seems like a lack of motivation or dedication on the part of the client, and at their own feelings that rise up when they cannot get the desired outcome. Threatened by the enormous challenge of an empathic effort to understand what the client is feeling, they retreat into science, talking about statistics in EBP studies to anxious wives, or the relationship between site of lesion and symptomatology. Rehab, by definition, is the place where people go to get better, not the place to integrate a new reality.

It is safe there, in the world of statistics and probabilities and research studies which cite percentages of improvement with this technique or another. How, then, to learn to love the place where things are totally unknown, and change the therapist narrative?

Hoping to address that a bit more in Philly.